20 KiB

Machi cluster "name game" sketch

- 1. "Name Games" with random-slicing style consistent hashing

- 2. Assumptions

- Basic familiarity with Machi high level design and Machi's "projection"

- Analogy: "neighborhood : city :: Machi chain : Machi cluster"

- Familiarity with the Machi chain concept

- Continue an early assumption: a Machi chain is unaware of clustering

- The reader is familiar with the random slicing technique

- 3. A simple illustration

- 4. Use of the cluster namespace: name separation plus chain type

- 5. In its lifetime, a file may be moved to different chains

- 6. Floating point is not required … it is merely convenient for explanation

- 7. Proposal: Break the opacity of Machi file names, slightly.

- 8. File migration (a.k.a. rebalancing/reparitioning/resharding/redistribution)

- 9. Other considerations for FLU/sequencer implementations

- 10. Acknowledgments

-- mode: org; --

1. "Name Games" with random-slicing style consistent hashing

Our goal: to distribute lots of files very evenly across a large collection of individual, small Machi chains.

2. Assumptions

Basic familiarity with Machi high level design and Machi's "projection"

The Machi high level design document contains all of the basic background assumed by the rest of this document.

Analogy: "neighborhood : city :: Machi chain : Machi cluster"

Analogy: The word "machi" in Japanese means small town or neighborhood. As the Tokyo Metropolitan Area is built from many machis and smaller cities, therefore a big, partitioned file store can be built out of many small Machi chains.

Familiarity with the Machi chain concept

It's clear (I hope!) from the Machi high level design document that Machi alone does not support any kind of file partitioning/distribution/sharding across multiple small Machi chains. There must be another layer above a Machi chain to provide such partitioning services.

Using the cluster quick-and-dirty prototype as an

architecture sketch, let's now assume that we have n independent Machi

chains. We assume that each of these chains has the same

chain length in the nominal case, e.g. chain length of 3.

We wish to provide partitioned/distributed file storage

across all n chains. We call the entire collection of n Machi

chains a "cluster".

We may wish to have several types of Machi clusters. For example:

- Chain length of 1 for "don't care if it gets lost, store stuff very very cheaply" data.

-

Chain length of 2 for normal data.

- Equivalent to quorum replication's reliability with 3 copies.

-

Chain length of 7 for critical, unreplaceable data.

- Equivalent to quorum replication's reliability with 15 copies.

Each of these types of chains will have a name N in the

namespace. The role of the cluster namespace will be demonstrated in

Section 3 below.

Continue an early assumption: a Machi chain is unaware of clustering

Let's continue with an assumption that an individual Machi chain inside of a cluster is completely unaware of the cluster layer.

The reader is familiar with the random slicing technique

I'd done something very-very-nearly-like-this for the Hibari database 6 years ago. But the Hibari technique was based on stuff I did at Sendmail, Inc, in 2000, so this technique feels like old news to me. {shrug}

The following section provides an illustrated example. Very quickly, the random slicing algorithm is:

- Hash a string onto the unit interval [0.0, 1.0)

- Calculate h(unit interval point, Map) -> bin, where

Mapdivides the unit interval into bins (or partitions or shards).

Machi's adaptation is in step 1: we do not hash any strings. Instead, we simply choose a number on the unit interval. This number is called the "cluster locator number".

As described later in this doc, Machi file names are structured into several components. One component of the file name contains the cluster locator number; we use the number as-is for step 2 above.

For more information about Random Slicing

For a comprehensive description of random slicing, please see the first two papers. For a quicker summary, please see the third reference.

Reliable and Randomized Data Distribution Strategies for Large Scale Storage Systems Alberto Miranda et al. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.226.5609 (short version, HIPC'11)

Random Slicing: Efficient and Scalable Data Placement for Large-Scale Storage Systems Alberto Miranda et al. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2632230 (long version, ACM Transactions on Storage, Vol. 10, No. 3, Article 9, 2014)

Hibari Sysadmin Guide, chain migration section. http://hibari.github.io/hibari-doc/hibari-sysadmin-guide.en.html#chain-migration

3. A simple illustration

We use a variation of the Random Slicing hash that we will call

rs_hash_with_float(). The Erlang-style function type is shown

below.

%% type specs, Erlang-style

-spec rs_hash_with_float(float(), rs_hash:map()) -> rs_hash:chain_id().I'm borrowing an illustration from the HibariDB documentation here, but it fits my purposes quite well. (I am the original creator of that image, and also the use license is compatible.)

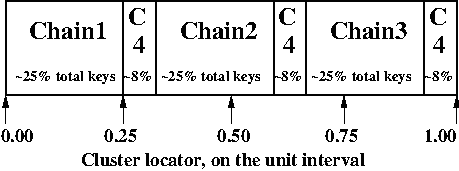

Assume that we have a random slicing map called Map. This particular

Map maps the unit interval onto 4 Machi chains:

| Hash range | Chain ID |

|---|---|

| 0.00 - 0.25 | Chain1 |

| 0.25 - 0.33 | Chain4 |

| 0.33 - 0.58 | Chain2 |

| 0.58 - 0.66 | Chain4 |

| 0.66 - 0.91 | Chain3 |

| 0.91 - 1.00 | Chain4 |

Assume that the system chooses a cluster locator of 0.05.

According to Map, the value of

rs_hash_with_float(0.05,Map) = Chain1.

Similarly, rs_hash_with_float(0.26,Map) = Chain4.

This example should look very similar to Hibari's technique. The Hibari documentation has a brief photo illustration of how random slicing works, see Hibari Sysadmin Guide, chain migration.

4. Use of the cluster namespace: name separation plus chain type

Let us assume that the cluster framework provides several different types of chains:

| Chain length | Namespace | Consistency Mode | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | normal |

eventual | Normal storage redundancy & cost |

| 2 | reduced |

eventual | Reduced cost storage |

| 1 | risky |

eventual | Really, really cheap storage |

| 7 | paranoid |

eventual | Safety-critical storage |

| 3 | sequential |

strong | Strong consistency |

The client may want to choose the amount of redundancy that its application requires: normal, reduced cost, or perhaps even a single copy. The cluster namespace is used by the client to signal this intention.

Further, the cluster administrators may wish to use the namespace to provide separate storage for different applications. Jane's application may use the namespace "jane-normal" and Bob's app uses "bob-reduced". Administrators may definine separate groups of chains on separate servers to serve these two applications.

5. In its lifetime, a file may be moved to different chains

The cluster management scheme may decide that files need to migrate to

other chains – i.e., file that is initially created on chain ID X

has been moved to chain ID Y.

- For storage load or I/O load balancing reasons.

- Because a chain is being decommissioned by the sysadmin.

6. Floating point is not required … it is merely convenient for explanation

NOTE: Use of floating point terms is not required. For example, integer arithmetic could be used, if using a sufficiently large interval to create an even & smooth distribution of hashes across the expected maximum number of chains.

For example, if the maximum cluster size would be 4,000 individual Machi chains, then a minimum of 12 bits of integer space is required to assign one integer per Machi chain. However, for load balancing purposes, a finer grain of (for example) 100 integers per Machi chain would permit file migration to move increments of approximately 1% of single Machi chain's storage capacity. A minimum of 12+7=19 bits of hash space would be necessary to accommodate these constraints.

It is likely that Machi's final implementation will choose a 24 bit integer (or perhaps 32 bits) to represent the cluster locator.

7. Proposal: Break the opacity of Machi file names, slightly.

Machi assigns file names based on:

ClientSuppliedPrefix ++ "^" ++ SomeOpaqueFileNameSuffix

What if some parts of the system could peek inside of the opaque file name suffix in order to look at the cluster location information that we might code in the filename suffix?

We break the system into parts that speak two levels of protocols, "high" and "low".

- The high level protocol is used outside of the Machi cluster

- The low level protocol is used inside of the Machi cluster

Both protocols are based on a Protocol Buffers specification and implementation. Other protocols, such as HTTP, will be added later.

+-----------------------+

| Machi external client |

| e.g. Riak CS |

+-----------------------+

^

| Machi "high" API

| ProtoBuffs protocol Machi cluster boundary: outside

.........................................................................

| Machi cluster boundary: inside

v

+--------------------------+ +------------------------+

| Machi "high" API service | | Machi HTTP API service |

+--------------------------+ +------------------------+

^ |

| +------------------------+

v v

+------------------------+

| Cluster bridge service |

+------------------------+

^

| Machi "low" API

| ProtoBuffs protocol

+----------------------------------------+----+----+

| | | |

v v v v

+-------------------------+ ... other chains...

| Chain C1 (logical view) |

| +--------------+ |

| | FLU server 1 | |

| | +--------------+ |

| +--| FLU server 2 | |

| +--------------+ | In reality, API bridge talks directly

+-------------------------+ to each FLU server in a chain.The notation we use

N= the cluster namespace, chosen by the client.p= file prefix, chosen by the client.L= the cluster locator (a number, type is implementation-dependent)Map= a mapping of cluster locators to chainsT= the target chain ID/nameu= a unique opaque file name suffix, e.g. a GUID stringF= a Machi file name, i.e., a concatenation ofp^L^N^u

The details: cluster file append

- Cluster client chooses

Nandp(i.e., cluster namespace and file prefix) and sends the append request to a Machi cluster member via the Protocol Buffers "high" API. - Cluster bridge chooses

T(i.e., target chain), based on criteria such as disk utilization percentage. - Cluster bridge knows the cluster

Mapfor namespaceN. - Cluster bridge choose some cluster locator value

Lsuch thatrs_hash_with_float(L,Map) = T(see algorithm below). - Cluster bridge sends its request to chain

T:append_chunk(p,L,N,...) -> {ok,p^L^N^u,ByteOffset} - Cluster bridge forwards the reply tuple to the client.

- Client stores/uses the file name

F = p^L^N^u.

The details: Cluster file read

- Cluster client sends the read request to a Machi cluster member via the Protocol Buffers "high" API.

- Cluster bridge parses the file name

Fto find the values ofLandN(recall,F = p^L^N^u). - Cluster bridge knows the Cluster

Mapfor typeN. - Cluster bridge calculates

rs_hash_with_float(L,Map) = T - Cluster bridge sends request to chain

T:read_chunk(F,...) ->… reply - Cluster bridge forwards the reply to the client.

The details: calculating 'L' (the cluster locator number) to match a desired target chain

- We know

Map, the current cluster mapping for a cluster namespaceN. - We look inside of

Map, and we find all of the unit interval ranges that map to our desired target chainT. Let's call this listMapList = [Range1=(start,end],Range2=(start,end],...]. - In our example,

T=Chain2. The exampleMapcontains a single unit interval range forChain2,[(0.33,0.58]]. - Choose a uniformly random number

ron the unit interval. - Calculate the cluster locator

Lby mappingronto the concatenation of the cluster hash space range intervals inMapList. For example, ifr=0.5, thenL = 0.33 + 0.5*(0.58-0.33) = 0.455, which is exactly in the middle of the(0.33,0.58]interval.

A bit more about the cluster namespaces's meaning and use

For use by Riak CS, for example, we'd likely start with the following namespaces … working our way down the list as we add new features and/or re-implement existing CS features.

- "standard" = Chain length = 3, eventually consistency mode

- "reduced" = Chain length = 2, eventually consistency mode.

- "stanchion7" = Chain length = 7, strong consistency mode. Perhaps use this namespace for the metadata required to re-implement the operations that are performed by today's Stanchion application.

We want the cluster framework to:

- provide means of creating and managing chains of different types, e.g., chain length, consistency mode.

- manage the mapping of cluster namespace names to the chains in the system.

- provide query functions to map a cluster

namespace name to a cluster map,

e.g.

get_cluster_latest_map("reduced") -> Map{generation=7,...}.

8. File migration (a.k.a. rebalancing/reparitioning/resharding/redistribution)

What is "migration"?

This section describes Machi's file migration. Other storage systems call this process as "rebalancing", "repartitioning", "resharding" or "redistribution". For Riak Core applications, it is called "handoff" and "ring resizing" (depending on the context). See also the Hadoop file balancer for another example of a data migration process.

As discussed in section 5, the client can have good reason for wanting to have some control of the initial location of the file within the chain. However, the chain manager has an ongoing interest in balancing resources throughout the lifetime of the file. Disks will get full, hardware will change, read workload will fluctuate, etc etc.

This document uses the word "migration" to describe moving data from one Machi chain to another chain within a cluster system.

A simple variation of the Random Slicing hash algorithm can easily accommodate Machi's need to migrate files without interfering with availability. Machi's migration task is much simpler due to the immutable nature of Machi file data.

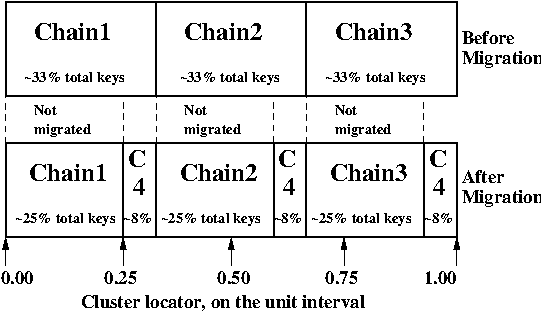

Change to Random Slicing

The map used by the Random Slicing hash algorithm needs a few simple changes to make file migration straightforward.

- Add a "generation number", a strictly increasing number (similar to a Machi chain's "epoch number") that reflects the history of changes made to the Random Slicing map

- Use a list of Random Slicing maps instead of a single map, one map per chance that files may not have been migrated yet out of that map.

As an example:

And the new Random Slicing map for some cluster namespace N might look

like this:

| Generation number / Namespace | 7 / reduced |

|---|---|

| SubMap | 1 |

| Hash range | Chain ID |

| 0.00 - 0.33 | Chain1 |

| 0.33 - 0.66 | Chain2 |

| 0.66 - 1.00 | Chain3 |

| SubMap | 2 |

| Hash range | Chain ID |

| 0.00 - 0.25 | Chain1 |

| 0.25 - 0.33 | Chain4 |

| 0.33 - 0.58 | Chain2 |

| 0.58 - 0.66 | Chain4 |

| 0.66 - 0.91 | Chain3 |

| 0.91 - 1.00 | Chain4 |

When a new Random Slicing map contains a single submap, then its use is identical to the original Random Slicing algorithm. If the map contains multiple submaps, then the access rules change a bit:

- Write operations always go to the newest/largest submap.

-

Read operations attempt to read from all unique submaps.

-

Skip searching submaps that refer to the same chain ID.

- In this example, unit interval value 0.10 is mapped to Chain1 by both submaps.

- Read from newest/largest submap to oldest/smallest submap.

- If not found in any submap, search a second time (to handle races with file copying between submaps).

- If the requested data is found, optionally copy it directly to the newest submap. (This is a variation of read repair (RR). RR here accelerates the migration process and can reduce the number of operations required to query servers in multiple submaps).

-

The cluster manager is responsible for:

- Managing the various generations of the cluster Random Slicing maps for all namespaces.

- Distributing namespace maps to cluster bridges.

- Managing the processes that are responsible for copying "cold" data, i.e., files data that is not regularly accessed, to its new submap location.

- When migration of a file to its new chain is confirmed successful, delete it from the old chain.

In example map #7, the cluster manager will copy files with unit interval

assignments in (0.25,0.33], (0.58,0.66], and (0.91,1.00] from their

old locations in chain IDs Chain1/2/3 to their new chain,

Chain4. When the cluster manager is satisfied that all such files have

been copied to Chain4, then the cluster manager can create and

distribute a new map, such as:

| Generation number / Namespace | 8 / reduced |

|---|---|

| SubMap | 1 |

| Hash range | Chain ID |

| 0.00 - 0.25 | Chain1 |

| 0.25 - 0.33 | Chain4 |

| 0.33 - 0.58 | Chain2 |

| 0.58 - 0.66 | Chain4 |

| 0.66 - 0.91 | Chain3 |

| 0.91 - 1.00 | Chain4 |

The HibariDB system performs data migrations in almost exactly this manner. However, one important limitation of HibariDB is not being able to perform more than one migration at a time. HibariDB's data is mutable. Mutation causes many problems when migrating data across two submaps; three or more submaps was too complex to implement quickly and correctly.

Fortunately for Machi, its file data is immutable and therefore can easily manage many migrations in parallel, i.e., its submap list may be several maps long, each one for an in-progress file migration.

9. Other considerations for FLU/sequencer implementations

Append to existing file when possible

The sequencer should always assign new offsets to the latest/newest file for any prefix, as long as all prerequisites are also true,

- The epoch has not changed. (In AP mode, epoch change -> mandatory file name suffix change.)

- The cluster locator number is stable.

- The latest file for prefix

pis smaller than maximum file size for a FLU's configuration.

The stability of the cluster locator number is an implementation detail that must be managed by the cluster bridge.

Reuse of the same file is not possible if the bridge always chooses a

different cluster locator number L or if the client always uses a unique

file prefix p. The latter is a sign of a misbehaved client; the

former is a poorly-implemented bridge.

10. Acknowledgments

The original source for the "migration-4.png" and "migration-3to4.png" images come from the HibariDB documentation.